My neighbors caused quite a stir in the news. They allowed their two children (10 and 6) take a 1.2 mile walk along Georgia Avenue (known above the Beltway as Route 97) from a park in the upscale Woodside neighborhood to their home near downtown Silver Spring, Maryland. For doing this, they were investigated by Child Protective Services and found to have engaged in “unsubstantiated child neglect.” My neighbors, the Meitivs, are part of the so-called free-range parenting movement – a movement that focuses on promoting (as appropriate) a child’s independence and self-reliance. As one person said about the name for the movement, “I like my children like my chicken: free-range.” I understand that these children were picked up by police again this evening.

Free-range parenting sees itself as an antidote to the “helicopter parenting” style that seems to predominate today. A world where parents must sign a permission slip to have a child eat an oreo. I have heard stories from college professors that they are now being contacted by parents of their students to inquire about why they received a certain grade on an exam or a paper, and parents signing off on their child’s courses. So the proverbial helicopter now is hovering past the age of majority.

A number of friends have asked me what I think about the Meitivs decision – whether I think CPS should have gotten involved for letting their children walk home. They are often surprised when I say that while I would not have allowed my children, even if typically developing, do what they Meitivs kids did, I have no problem with it. The fact is that we simply can’t live in a world where we get to continually micromanage and judge the parenting decisions of others. While I would like to believe that people who believe CPS was necessary here are doing so out of a genuine feeling of concern, it is easy to see where that kind of “caring,” is, as the Shins say, creepy. Or even worse, interfering can be actually detrimental to the child.

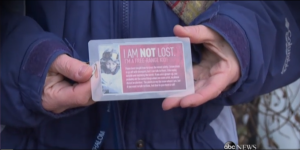

I think friends ask my opinion because they know that parents of special needs children (particularly those with medical needs) have a special appreciation for this problem. While parents of “normal” children are allowed, in relative terms, a wide berth to raise their children, we are not. From the moment our child is born, the “system” micromanages every aspect of our lives — they obviously need to, because we could not even procreate a “normal” child, right?

One area where this sort of interference is most unwelcome is in the area of medical treatment. Nowhere is the denial that reasonable minds can differ about treatment, and sometimes diagnosis, more dangerous and toxic. Two recent examples of that were the arrest of the parents of a boy with rare brain caner who was removed, against medical advice, by his parents from a hospital and taken to Spain to undergo an “experimental” treatment. It just so turns out, that treatment may have saved him. Or a much more dramatic example is the horrible drama that unfolded for Justina Pelletier, a 14 year-old girl removed from her family because she was originally diagnosed with mitochondrial disease and sent to another institution for some adjunct treatment. Once there, some new doctor developed the opinion that Justina was not really ill – she had a “somataform disorder,” which is a fancy way of saying it was all in her head. The doctors at the new hospital were so persuasive, Justina was removed from her family’s care, and they were not allowed to see her for almost a year until they raised sufficient money to hire a lawyer and fight back.

My husband and I have occasionally been pressured to do certain things or not do certain things for our children, and we have always governed ourselves according to our own convictions. Watching what is happening makes me wonder, though, if the day will come when someone has enough hubris to try and say that they know better than we do how to care for our children. Maybe that day is coming, or maybe it has already arrived and I haven’t really felt any deleterious effects from it, save being judged. What I do know is that “well meaning” people are often the ones who are the most dangerous and it is them I watch most closely, like a helicopter.